You’re doing everything right. You’re consistent with your workouts, you’re pushing yourself, and you’re trying to eat well. But when you look in the mirror or check your performance numbers, the progress you expect just isn’t there. It’s a frustrating scenario, and the culprit might be an invisible force you’re not tracking: high stress. Understanding how high stress impacts workout results is the first step to breaking through a plateau you didn’t even know was stress-induced.

At Pillar, we view your body as a laboratory, not a battlefield. Every factor, including your mental state, is a variable in your experiment. Stress isn’t just a feeling; it’s a physiological response that can directly sabotage the outcome of your hard work. This guide will explain the science behind why this happens and provide a clear framework for managing it.

The Stress Equation: Your Body’s Capacity is Finite

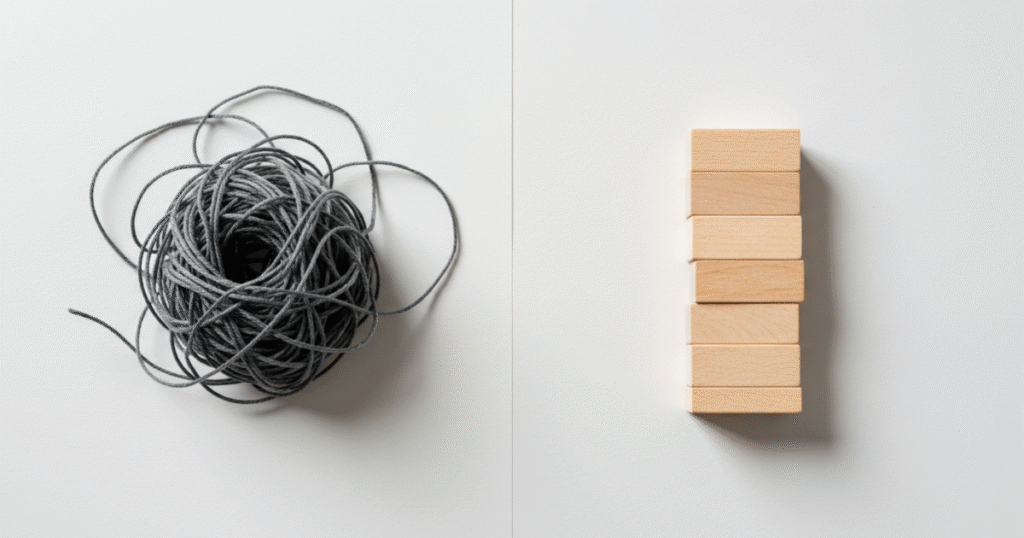

Think of your body’s ability to handle stress as a single bucket. Every stressor in your life—a deadline at work, a family argument, financial worries, and even a tough workout—goes into this one bucket. A workout, or Stimulus as we call it in the Pillar Methodology, is a planned, beneficial stressor designed to trigger positive adaptation.

However, your body doesn’t distinguish between the source of the stress. When chronic life stress keeps your bucket perpetually close to overflowing, adding the physical stress of a workout can cause it to spill over. This state of overload is where your progress stalls and your health can decline.

How High Stress Impacts Workout Results: The Science

When your stress bucket overflows, a cascade of negative hormonal and physiological changes begins, directly interfering with your body’s ability to recover and build muscle. This is where the Regenerate pillar becomes the most important part of your experiment.

The Cortisol Connection: Your Gains Under Attack

When you’re chronically stressed, your body produces an excess of cortisol, often called the “stress hormone.” While cortisol is necessary in small doses, elevated levels create a catabolic (breaking down) environment in your body. This means that instead of building new muscle tissue after a workout, your body may actually break it down for energy (1). You’re putting in the work to build, but your internal hormonal environment is actively working to deconstruct.

Impaired Recovery and Regeneration

Adaptation doesn’t happen in the gym; it happens during recovery. High stress is a direct assault on this critical process. Studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of psychological stress experience significantly worse recovery and more muscle soreness after strenuous exercise (2).

Furthermore, stress often disrupts sleep. Sleep is your body’s prime time for regeneration, releasing growth hormone and repairing damaged muscle fibers. When stress leads to poor sleep, you rob your body of its most crucial recovery tool, blunting your fitness adaptations.

Compromised Nutrient & Energy Management

The Nourish pillar is about supplying your experiment with the right materials. Stress throws a wrench in this process. Cortisol can increase cravings for highly palatable, nutrient-poor foods. Research indicates that chronic stress and high cortisol levels are linked to increased cravings for sugar and fat, which can lead to weight gain and hinder your body composition goals (3). It effectively encourages your body to store energy as fat rather than use it to build muscle.

The Pillar Protocol for Managing Stress

Recognizing the problem is half the battle. Now, you need a protocol to manage this variable. Instead of fighting stress, you will run an experiment to manage it.

Step 1: Audit Your Stressors

The Audit pillar is the engine of progress. You cannot manage what you do not measure. Take an honest inventory of your life.

- What are your primary non-training stressors? (Work, relationships, finances, etc.)

- How is your sleep quality on a scale of 1-10?

- Are you relying on stimulants like caffeine to get through the day?

Write these down. Seeing them on paper is the first step to acknowledging them as real data points in your experiment.

Step 2: Prioritize the Regenerate Pillar

When life stress is high, your top priority must shift to regeneration. This isn’t optional; it’s essential for progress.

- Protect Your Sleep: Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Make your room dark, cool, and quiet. Avoid screens an hour before bed.

- Practice Active De-Stressing: Dedicate 10-15 minutes each day to an activity that lowers your stress. This could be meditation, deep breathing exercises, a light walk in nature, or journaling.

- Implement Active Recovery: On rest days, engage in low-intensity movement like walking or gentle stretching to promote blood flow and reduce soreness without adding significant stress to your system.

Step 3: Adjust Your Stimulus

During periods of exceptionally high life stress, it is a strategic and intelligent decision to adjust your training. This is not failure; it’s a recalibration of your experiment.

- Reduce Volume or Intensity: You might shorten your workouts, reduce the weights by 10-15%, or do fewer sets.

- Focus on Form: Use these periods to perfect your technique with lighter loads.

- Do Not Stop: The goal is to scale back, not stop entirely. A Minimum Effective Dose (MED) workout is far better than a missed day, which provides no data.

Conclusion: Take Control of the Invisible Variable

Stress is not just a feeling—it’s a powerful physiological force that can dictate the results of your hard work. By understanding how high stress impacts workout results, you can shift your perspective from battling frustration to conducting a more intelligent experiment.

Reframe your approach. When you notice a plateau, don’t just add more Stimulus. Instead, perform an Audit on your stress and double down on your commitment to the Regenerate pillar. By managing your body’s total stress load, you create the physiological environment where your hard work can finally pay off.

Sources

- Hill, E. E., Zack, E., Battaglini, C., Viru, M., Viru, A., & Hackney, A. C. (2008). Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. Journal of endocrinological investigation, 31(7), 587–591.

- Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., & Bartholomew, J. B. (2012). Psychological stress impairs recovery from strenuous exercise: a prospective study of collegiate rowers. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 26(12), 3421–3429.

- Chao, A. M., Jastreboff, A. M., White, M. A., Grilo, C. M., & Sinha, R. (2017). Stress, cortisol, and other appetite-related hormones: Prospective prediction of 6-month changes in food cravings and weight. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 25(4), 713–720.